Violating ISP with Constructor Injection

One problem with IoC containers is that they facilitate ISP violations through constructor injection.

The interface-segregation principle (ISP) states that no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use.

Let's take a look at some typical, and very terrible, code. I'm actually astonished at how many anti-patterns can be put into so few lines of code (AP/LOC?). It makes my eyes bleed.

public interface ICustomerService

{

Customer GetCustomer(int id);

void CreateCustomer(Customer customer);

}

public interface IRepository<T>

{

T GetById(int id);

void Add(T entity);

}

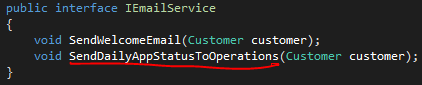

public interface IEmailService

{

void SendWelcomeEmail(Customer customer);

void SendDailyAppStatusToOperations(Customer customer);

}

public class Customer

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

public class CustomerService : ICustomerService

{

private readonly IRepository<Customer> _repository;

private readonly IEmailService _email;

public CustomerService(

IRepository<Customer> repository,

IEmailService email)

{

_repository = repository;

_email = email;

}

public Customer GetCustomer(int id)

{

return _repository.GetById(id);

}

public void CreateCustomer(Customer customer)

{

_repository.Add(customer);

_email.SendWelcomeEmail(customer);

}

}

About the only thing that code is missing is an ICustomer class. Don't laugh. Interfaces on POCOs/DTOs have been spotted in the wild. Let's not dwell on this code or how it can be changed.

How does it violate ISP?

CustomerService never uses SendDailyAppStatusToOperations, and yet it's called out as a dependency.

To be clear, this isn't caused by IoC containers. We programmers tend to have a false sense of security that if we have interfaces, we're following best practices. We're coding to the interface! Our blind usage of layered architectures, "noun services", and endless abstractions are more to blame.

The IEmailService is very typical in systems I run across. Why aren't these methods on separate interfaces? My guess is that the tools (containers, R#, moq, scm, etc) are all subtly pushing us in this direction.

Uggggh. I could create another interface, but then I'd have to go wire it up/mock it/inject it when I have this interface that already makes sense. I mean, it's all about emailing, right? And there's this other service that uses both methods. How many different interfaces am I going to have to create here?!? I'll have to add more files. Gah, I just know there will be merge conflicts on the project file! How about I just add this one method here and type alt-enter (R# ftw!).

Now, let's go a step farther. Let's expand the definition of ISP to the entire contract of an object, including it's constructor.

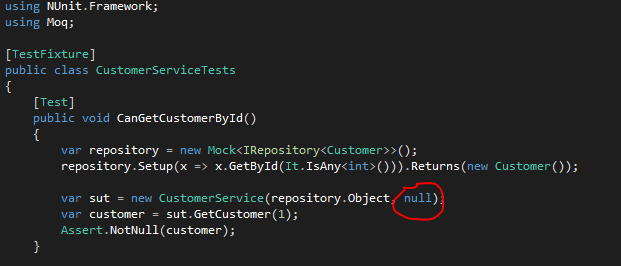

I've seen, and written, the following test many times:

Null is passed for a "dependency" and the test still passes.

Before you dismiss this as a straw man argument, how did I know I could pass null for IEmailService? Isn't that secret knowledge of the internal workings of the class? If I need to change IEmailService, does it affect CustomerService?

If IEmailService isn't required for "getting a customer", when is it required? Why is it a dependency for "getting a customer"?

This is where I lay some blame on the IoC container. If we were "new-ing" up classes manually, this would obviously be silly. Someone working on "displaying customer info" feature would balk at having to construct an IEmailService class to pass. You can immediately see that you need a different construct for dealing with "displaying customer info" as opposed to "creating a new customer". In anger, the programmer will probably supply null and commit (hey, didn't break the build!). You could argue you should have another constructor that only takes one arg, but that's not what your container is going to use. If you have a constructor with one arg, then you need some guard clauses on methods that use IEmailService to tell the caller to use the correct constructor.

The container makes this pain disappear, and that is A Bad Thing.

Imagine the business wants to "Send an email when the customer is accessed on Tuesdays". Someone goes and codes it. Wait, why are all these "Get Customer" tests failing [every Tuesday]? You mean I have to go fix all those? Yes. Yes you do.

One could argue that this was bad test writing. You should always supply a mock of all dependencies!

Yet isn't part of TDD writing the minimum code to make the test pass? Besides, should doesn't make it so.

So, while we're going through our test suite creating mocks where we didn't need them before, let's think about this a bit.

Is the "Customer Service class" dependent on IEmailService or is the "Create Customer method" dependent on IEmailService?

I'd say the latter, but that leads us back to 8 lines of code.

As further evidence, a thought experiment: why not inject every possible dependency and then it will already be there if we ever need it? We can use better tooling to auto-mock them for easy testing.

Pretty horrible idea, right? Why is a dependency we only need some of the time better?

Too many dependencies contribute to SRP violations as well, but I'll save that for a future post. As a preview, Jimmy Bogard pointed out on twitter that you can't really "unit test" classes written in this manner.